Autran Group Special: What to Expect in 2026

As 2026 begins, the post-Cold War international order is undergoing significant transformation as major powers and regional actors increasingly pursue competing visions of global governance, with overlapping spheres of influence replacing the once-dominant multilateral framework, whilst economic fragmentation through tariffs, export controls, and alternative financial mechanisms advances strategic objectives. In an era where multiple power centres coexist without a universally accepted rulebook, how will the international community navigate transnational challenges that require coordinated responses?

GLOBAL

Takamaro H. & Raymond P.

12/31/202525 min read

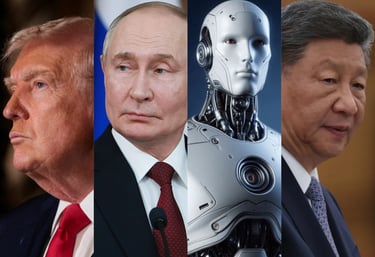

On the very cusp of 2026, the world finds itself at a crossroads once again, largely due to the cumulative erosion of the political order that has stood since the end of the Cold War. Over the past year, Russia's protracted war in Ukraine has established the idea that borders can once again be modified through military force. Contemporaneously, the Trump administration has rejected the United States' role as a "global policeman", instead opting for a strategy of restraint and selective engagement that prioritizes American interests, and pressures allies to shoulder greater militaristic and economic burdens. This shift accelerates the emergence of overlapping spheres of influence in which Washington, Beijing, Moscow, and a set of regional middle powers each seek to consolidate their own rules, security arrangements, and economic networks, often at the expense of multilateral institutions that once mediated disputes. Traditional deterrence frameworks are being tested on an international scale. Tensions in the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and the borderlands of Ukraine, have all revealed gaps between declaratory policy and actual capabilities. These strains on global security intersect with a global economy that has become increasingly weaponized, with tariffs and other retaliatory trade measures being used as means of exerting economic policy on other nations. Export controls on advanced technologies such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence, as well as growing experimentation with sections and alternative financial channels, all ensure that regional conflicts are heavily intertwined with economic fragmentation and technological competition. In 2026, many will notice that the absence of a shared framework of economic interdependence and the management of political rivalries will leave international politics shaped more by competing ambitions from a vast cast of actors rather than a universal body of norms.

Ukraine at an Inflection Point: Peace, Partition, or Prolongation?

When Russian forces launched their full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this marked a pivotal moment in European history. Since the first soldiers made landfall in early 2022, the European security order that emerged after the Cold War has been in a state of constant erosion. Four years on, the conflict has transformed from what was initially framed as a simple "special military operation" into a grinding war of attrition that has reshaped energy markets, shattered longstanding ideas concerning deterrence, and tested the long-term viability of Western political thought. For President Trump, who campaigned on a swift end to the war in Ukraine, and rejects the notion of the United States serving as the world's "global policeman," the persistence of the conflict into 2026 is a double-edged sword, presenting both political liabilities and potential opportunities. The question is no longer merely whether Ukraine can restore its original borders established after the fall of the Soviet Union, but whether a settlement emerging in 2026 will be one that cements Russian territorial gains, preserves Ukraine as a self-sufficient state, or leaves Europe with a frozen conflict at the heart of the continent.

From Washington's perspective, the "ceasefire imperative" is driven by domestic policies as much as by battlefield realities. For Trump, a significant amount of political capital lies on his promise of ending "endless wars," and the continuation of a costly European conflict risks alienating fiscal conservatives as well as the broader general public, which has grown weary of wars stemming from foreign entanglements after Iraq and Afghanistan. Reports that the White House is pressuring Kyiv to accept peace plans that involve the concession of occupied territory to Russia demonstrate the degree to which Washington has shifted from viewing these conflicts through a lens based in Western principles to a more transactional cost-benefit lens. At the same time, the gradual reduction of American deployments and military exercises in Eastern Europe sends a clear signal to Moscow that American attention is finite and increasingly drawn toward China and domestic priorities, thereby weakening the very deterrence architecture that was hastily constructed after the 2022 invasion. This stands in stark contrast to the instincts of many European governments, which still see a sustained Ukrainian resistance as the only reliable means of preventing Russian expansionism from creeping further west.

On the ground, however, the lines of contact tell a story of slow but tangible Russian advances, particularly in the east. By late 2025, Russian forces had consolidated control over the vast majority of Luhansk and close to 70 percent of Donetsk, while making incremental gains in parts of the Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv regions, aided by superior artillery stocks and a willingness to absorb heavy casualties. Despite this, Russia’s ability to sustain high-intensity operations is increasingly constrained. Analysts note that Moscow is unable to build out a strategic reserve, and is relying on constant recruitment cycles to maintain the current level of assault, a model that may become harder to sustain as casualties mount and weariness of continued war efforts grows. Meanwhile, Ukraine faces an unfavorable attritional balance due to depleted air defenses, ammunition shortages, and demographic strain. Thus, without continuous replenishment from Western allies, Kyiv risks being slowly pushed out of remaining strongholds in eastern Donetsk and parts of the southeast. It is against this backdrop that President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has signaled some openness to territorial concessions in exchange for internationally monitored demilitarized zones and reciprocal Russian withdrawals, a position that would have been politically unthinkable in the first year of the war.

Military experts and Ukrainian journalists alike increasingly converge on the view that 2026 will be the year in which both sides push each other near their limits. On the Russian side, continued offensive operations will either require escalating recruitment efforts or accepting that further large-scale territorial gains are unlikely without disproportionate costs. For Kyiv, the incentive is to demonstrate enough battlefield resilience to convince both Moscow and Western capitals that Ukraine remains a viable security partner rather than a failed buffer state, even as domestic politics becomes more turbulent amid corruption scandals and calls for wartime elections. In this sense, militaristic strategies have become increasingly intertwined with diplomatic efforts. Every kilometer of territory lost or held in contested regions will shape the narrative strength each side brings into negotiations that may open in the second half of 2026.

The negotiation scenarios that analysts sketch out for the next year reflect varied assessments of military balance and differing political narratives about what constitutes "victory" for either side. For Moscow, the best-case scenario would be a war that ends in the first half of 2026 with Russia in control of most of Luhansk, Donetsk, and parts of southern Ukraine, coupled with some form of Ukrainian acknowledgement of these territorial losses. This would allow the Kremlin to claim that its publicly proclaimed objectives have been realized. In Kyiv's view, a better scenario would be the emergence of an opportunity for a fairer agreement in the latter half of 2026, but only if the Kremlin concludes that continuing this war risks further economic deterioration and mounting disapproval among the general public. However, independent military and political analysts agree on a more cautious baseline, stating that the most realistic short-term prospect is a temporary cessation of hostilities or partial ceasefire by late 2026, which could be followed by months, if not years, of negotiations over borders, security guarantees, and sanctions relief. A more pessimistic scenario that has been widely discussed on both sides entails a protracted stalemate in which negotiations continue in parallel with low-intensity fighting along entrenched lines, creating the conditions for a new frozen conflict on Europe’s eastern flank.

These potential diplomatic outcomes cannot be separated from a broader structural shift underway within NATO and other allied nations. The Trump administration's insistence that European allies assume the majority of NATO's conventional defense burden by 2027, as well as the implicit threat to scale back American participation in future deployments if these conditions are not met, has already raised uncomfortable questions in European member states about the long-term credibility of Article 5. Firms that specialize in defensive and military technology will also be hurt by these developments as they experience greater strain due to higher demands of rearmament from NATO. Further destabilization in pre-existing orders has also resulted from the sense of exclusion from core decision-making among European states. Reports have shown that Trump and Putin have engaged in backchannel discussions about potential settlement parameters, with limited consultation of key NATO allies. For many in Central and Eastern Europe, this brings back memories of great-power bargaining over the heads of smaller states, a practice that was previously assumed to be a relic of the 20th century. For Poland and the Baltic states, whose defense strategies hinge on Ukrainian resilience and strong commitment from the US, the prospect of a deal between the US and Russia that trades Ukrainian territory for a vague ceasefire is viewed less as an end to war and more as the prelude to a new era fraught with insecurity.

A negotiated settlement that codifies Ukrainian territorial losses while stopping short of offering clear support from NATO's member states or robust guarantees of international security risks creating the very gray zones that European policies sought to eliminate after the Cold War. In such a scenario, Ukraine would remain outside the alliance's formal security umbrella, flanked by demilitarized zones along its eastern and southern borders that constrain its ability to defend itself, while Russia would retain leverage through its control over occupied territories and its capacity to continue hostilities at will. For European states on NATO's eastern frontiers, this outcome would likely accelerate moves towards independent deterrence postures as confidence in American security guarantees erodes. At the same time, a settlement titled in Moscow's favor, particularly one perceived as being imposed under US pressure, would deepen fractures within NATO, embolden Russian narratives about Western weakness, and raise uncomfortable questions about whether similar pragmatic compromises might be on the table in other theaters such as the Baltic Sea or the Black Sea.

Beyond the immediate European theater, the way the Ukraine war is brought to a close in 2026, or allowed to persist, will have a significant impact on the global system. For Russia, a deal that guarantees substantial territorial gains while easing sanctions would be read in Moscow as a validation of a strategy in which perseverance and willingness to sustain pain will ultimately prevail over Western solidarity, thus encouraging similar strategies in the future. American credibility would suffer not only in Europe but also in other regions of the world. Allies in Taiwan, Japan, and Southeast Asia are watching closely to see whether Washington is prepared to withstand economic and political costs in defense of the principles it upholds in international affairs. In much of the Global South, where skepticism of Western double standards remains high, a settlement seen as legitimizing border changes achieved through militaristic force would reinforce the perception that the international system rewards this behavior, provided that it is executed with sufficient power and diplomacy. 2026 thus emerges as a pivotal year in which the timelines of battlefield exhaustion, domestic affairs in Washington and Moscow, and a fragmenting world order converge. The next year will reveal whether Ukraine becomes the precedent for a new era of uncertainty, or a painful reminder of boundaries that should not be ignored.

A Year of Resolution for the Taiwan Crisis?

Ever since the conclusion of the First Opium War in 1842, the lands considered traditionally to be a core part of the Chinese nation have remained fractured and in different hands. The Communist Party of China’s (CPC) reunification of Mainland China in 1949 and the return of Hong Kong and Macau to Chinese control in the 90s have consolidated the CPC’s claim as the true inheritor of the Chinese “Mandate of Heaven” from the preceding Qing dynasty. Yet a thorn remains in the form of the self-ruling island of Taiwan, which stands firmly Western in its values, system of government, and alignment, and has agitated repeatedly for independence. The return of the island of Taiwan to CPC control would be a crowning jewel for Chinese ambitions, and would firmly consolidate China’s position as the sole great power in the Orient. The United States has historically stood in the way of China’s desire to retake the island. However, President Trump’s hostility towards the idea of America as the “global policeman” and proclivity for working with authoritarian governments as opposed to acting against them implies that a possible resolution to the “Taiwanese Question” may very well transpire in 2026.

While the United States has, as a principle, supported the self-governing status of Taiwan for myriad reasons, ranging from serving as a critical base for projecting military power and protecting key supply chains to having it stand as a “showcase” of Western liberal democracy in the East, the strongest reason for which American support continues, especially with the end of the Cold War and the advent of the Information Age, is one of pure practicality and realpolitik: that of semiconductor chips, and Taiwan’s ability to produce the world’s most advanced chips through TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company). The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) as a rapidly growing and increasingly powerful technology in 2022 and the dependency of AI on such semiconductors has, by proxy, made Taiwan critical to the AI arms race.

Given Trump’s hostility towards neoliberal ideas of America propping up liberal governments worldwide, general capriciousness towards issues like Taiwan and Ukraine, and predilection for approaching politics in a manner that a businessman would with any “business deals”, all eyes are on the summit planned by Trump in Beijing in early 2026 with President Xi Jinping of China.

2026 stands out as a critical year for Trump, as the mid-term elections will take place from March to November. Losing control of either the Senate or the House of Representatives would severely limit Trump’s political power and ability to impose any of his original agendas. Trump already faces widespread political dissent from both ends of the American political spectrum over his mishandling of and role within the Epstein scandal, arguably one of the worst cases of political corruption in modern American history. While, realistically speaking, it is unlikely that any form of “resolution” of the Taiwan crisis would be able to ameliorate the damage to the faith of voters in Trump and the Republican Party (which was brought down by a domestic, and perhaps even existential crisis for the American nation), Trump would nevertheless seek to maximise his credibility in the eyes of voters by enforcing his agenda of removing America from the world’s conflicts in a manner that benefits America the most.

A pragmatic solution that may emerge at the 2026 Beijing summit, if any at all, may involve the arrival of a compromise on the Taiwanese question that may, in turn, potentially signal a resolution after more than 75 years of cross-strait tensions. Such a compromise may involve the shifting of TSMC’s facilities and technology over to the United States, with Trump in turn giving China the green light to assert its control over Taiwan.

While such a solution is likely to displease the vast majority of Congress, it may appeal to the American public’s distaste for American interventionism, which has skyrocketed since the Iraq War of 2003, along with subsequent American debacles in the Middle East, and public dissatisfaction with the allegedly excessive financial support given to Ukraine. Additionally, shifting TSMC’s production over to the United States would create jobs and significantly reduce costs for American businesses dependent on semiconductors, which Trump could then reframe as an economic victory.

It is however critical to note that Trump has authorised $1 billion in funding for defence cooperation with Taiwan in December 2025 through the National Defense Authorisation Act 2026, while his National Security Strategy also explicitly states that “deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority”. That said, this could in turn be construed as a potential bargaining chip between Trump and Xi for any business and trade concessions, with Trump being entirely capable of reversing course on military support for Taiwan in the course of 2026.

Another interesting angle to consider is what could potentially happen in the event of there not being a resolution to the Taiwan crisis in 2026; several news sources have alleged that China has been planning a potential invasion of Taiwan set for 2027, although, as with any form of news concerning China that reaches the West, it must be taken with great scepticism, given the notorious informational opacity of Chinese politicking. Any form of military escalation from China that would amount to a state of armed conflict is likely to incite a similar level of umbrage as was seen in the case of Russia when it invaded Ukraine in 2022 from Western nations. That said, in terms of practical consequences, given the increasingly cold relations between the Trump administration and the EU (as exemplified by the US imposing sanctions onto former EU bureaucrats), along with the EU already struggling to present a united front against Russia vis-à-vis Ukraine and the EU’s dependency on China as a trade partner, it is likely that the EU’s reaction to even a full-blown invasion of Taiwan by China would be muted. The most outrage is likely to originate from the Anglosphere, which includes the United States and the CANZUK nations. The most critical factor here is that of how Trump would react, although this in and of itself is also dependent on how China chooses to approach said military action. Two likely options exist, with one being that of an outright amphibious invasion of the island across the strait, and the latter being one of a total embargo of the island by both sea and air. Invariably, Trump would be forced to react more strongly to the former by the political establishment; this would however run contrary to Trump’s policy of not involving America in any further wars, and may risk potential escalation into a global conflict, with the latter being a possibility that Trump would not want staining his already tainted legacy.

All of this conjecture is, of course, dependent on whether China would even choose to act in 2027 to begin with. China’s perceptions of when to act are likely dependent on how they predict the incumbent American administration would react. Given Trump’s lacklustre response to Ukraine, should China seek to end the crisis by military means, it is clear that acting during a Trump presidency would be the least likely to result in any form of escalation on the American side; waiting past 2028 and the election of a new president, be it Republican or Democrat, would in turn risk having to face off with a more establishment-oriented administration that would naturally be more interventionist in nature.

2026 thus stands out in being a year where a likely resolution to the Taiwan crisis may finally emerge, although whether this resolution will be peaceful or violent in nature remains to be seen. There remains the possibility that China believes that it yet possesses the cards to take Taiwan by any means, and that a decade or more may pass before any legitimate attempt is made to achieve total reunification.

Trump’s Transactional Realignment: Technology, Tariffs, and the End of the Liberal Trade Order

Since returning to office in January 2025, President Trump has sought not merely to tweak the global trading system, but to overturn the basic premise that open markets and multilateral institutions are inherently beneficial to American power. In his public rhetoric and in the text of his 2025 National Security Strategy, he has cast tariffs, sanctions, and regulatory pressure as tools of national revival rather than distortions of an otherwise liberal economic order. Under this vision, economic interdependence is no longer treated as a guarantee of peace, but as a vulnerability to be exploited, with the United States weaponizing access to its market, currency, and technology in a bid to re-anchor global competition on terms more favorable to Washington. The overarching impact will be the transformation of economic statecraft from a supporting instrument of foreign policy into one of its primary terrains, with 2026 emerging as the year in which this experiment will begin to demonstrate whether it produces strategic advantage or systemic blowback.

An essential aspect of this shift has been Trump's conversion of the tariff from a tactical bargaining chip into a standing instrument of geopolitical leverage. In the past year, average US tariffs have risen by several hundred percent compared to pre-Trump levels, with duties on Chinese goods in particular extending far beyond the measures of the late 2010s trade war. New and proposed measures include a 25% tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico, a 10% baseline on Chinese products, and a 25% duty on European steel and aluminum, alongside threats to impose tariffs of up to 200% on signature European exports such as wine and champagne. Rather than temporary pressure points that could fade with concessions, these have been framed as structural features of a new commercial order explicitly tied to demands that allies spend more on defense, host reshored manufacturing, and align with US efforts to secure semiconductor and AI supply chains from Chinese influence. In this sense, the tariff regime acts as both punishment for perceived freeloading and as a signaling device that access to US demand now comes with clear geopolitical strings attached.

The economic impact of this strategy has already manifested, and 2026 will be the year in which its secondary effects will ripple across the global economy. International institutions have revised their forecasts downward, with the OECD now projecting global growth of roughly 2.9% for 2025–2026 and warning that a further 10 percentage point increase in tariffs could shave around 0.3% off world GDP within two years. For American households, estimates suggest that the combined tariff wedges could potentially increase annual expenses by as much as 3,900 dollars, due to higher prices on imported consumer goods and intermediate inputs. This could push headline inflation up by as much as 2.8% absent offsetting policy interventions. Because lower-income and middle-income families devote a greater share of their income to tradable goods, these measures function as a de facto regressive tax, offsetting some of the redistributive rhetoric that accompanies Trump's call to revive domestic manufacturing. A December business survey reinforces this pessimism, finding that a narrow majority of executives and analysts now view recession or near-recession scenarios in 2025-2026 as the most probable outcome, and for the first time since late 2022, the share expecting conditions to deteriorate exceeds the share anticipating improvement.

The external reverberations are particularly acute in export-oriented economies whose industrial models were built on reliable access to the US market. Nowhere is this clearer than in the European automotive sector, where integrated supply chains run through Mexico and Canada and are thus highly exposed to Trump's across-the-board North American tariffs. Key industry leaders warn that up to 780,000 jobs in Germany alone could be at risk if the US duties and retaliatory measures disrupt cross-border production and make European vehicles uncompetitive in their largest non-EU market. Similar dynamics threaten manufacturers in East Asia, where firms must navigate between US demands to decouple from China and the continued lure of Chinese demand, while financial markets are forced to price in the risk of tariff escalation as a semi-permanent feature of the global environment rather than a passing episode. The danger for Trump is that a policy framed domestically as a rebalancing tool may, if mishandled, tip both the United States and its closest partners towards slower growth just as geopolitical competition requires expensive investments in defense and technology.

Predictably, China has not remained passive in light of this new economic pressure, but has accelerated its longstanding effort to reduce strategic dependence on Western markets and technologies. Over the past decade, Beijing has reoriented trade towards the Global South, becoming the largest trading partner for more than ninety countries and locking in privileged access to commodities, infrastructure projects, and political goodwill through initiatives such as the Belt and Road. At the same time, China now accounts for more than a quarter of global industrial R&D and roughly half of worldwide technology patent applications, reflecting an explicit state‑led push to climb further up the value chain. Its current account surplus is projected by some analysts to approach 1% of the global GDP in the next three to five years, an unprecedented concentration of surplus that Beijing can deploy as capital and credit in regions where American influence has waned. The Trump administration has responded by tying prospective trade deals to forced foreign direct investment, deregulating domestic industry to lure manufacturing back to US soil, and tightening export controls on advanced chips and dual‑use technologies, thereby hastening an economic division into a US‑aligned production bloc centered on semiconductors, AI, and green technology, and a China‑aligned bloc anchored in mineral extraction, conventional manufacturing, and infrastructure finance.

This contest is increasingly playing out in the digital realm, where rules over data and services are becoming as strategically important as tariffs on physical goods. Governments across advanced and emerging economies are tightening controls on online content, mandating local data storage, and experimenting with new forms of taxation on digital services as they grapple with the power of multinational technology firms and the security implications of data flows. In surveys of senior executives, roughly 72% now cite data sovereignty and regulatory compliance as their most significant AI-related challenge heading into 2026, a sharp increase from similar surveys just half a year prior. In conjunction with these developments, a growing number of states are investing in national AI clouds and domestically controlled foundation models in pursuit of what is increasingly termed "AI sovereignty." Services trade, which accounts for around 13% of US exports and includes cloud computing, digital platforms, and financial technology, is thus moving to the front lines of geopolitical struggle, as rival regulatory regimes and divergent content standards fragment what was once treated as a single, global internet into implicit spheres of digital influence.

Overlaying all of this is a deliberate attempt by Trump to realign America's security relationships in ways that shift both financial costs and political risks onto allies, with Europe bearing the brunt of these expectations. In late 2025, Washington quietly informed NATO partners that by 2027 it expects European states collectively to assume responsibility for the majority of the alliance's conventional defense burden, particularly on the continent's eastern frontiers. European officials have pushed back, noting that even with recent increases in defense spending, production timelines for munitions, air defense systems, and other militaristic resources, may stretch well into the 2030s. Many believe that there is no realistic way to replicate within a few years the specialized American capabilities that underpin NATO's current deterrent posture. Nevertheless, the Trump administration has signaled that failure to meet these benchmarks could trigger a drawback on rotational deployments, a reduction in American participation in NATO planning structures, and a more selective approach to future security guarantees, even as it wields tariffs and the threat of further economic penalties to press European governments toward greater military outlays.

Taken together, Trump's approach to economic statecraft pushes the international system toward a world in which market access, technology flows, and security guarantees are explicitly contingent on alignment with Washington’s strategic priorities. For developing economies, this creates a precarious environment in which alignment choices carry steep opportunity costs. Siding too closely with the US comes with the risk of losing access to lucrative Chinese markets, while leaning towards Beijing can trigger hefty sanctions or exclusion from US-centered supply chains, all against the backdrop of tariff-driven increases in import costs that erode competitiveness and strain fragile social contracts. For Europe and other traditional allies, the combination of trade pressure and the shifting of defensive burdens forces a binary choice between accepting a costly and politically contentious drive towards strategic autonomy, or accepting an increasingly transactional dependence on a United States that is willing to use economic coercion against friends and competitors alike. For the broader Global South, China's expanding commercial dominance and the weakening of multilateral trade disciplines mean that access to both Western and Chinese markets is now mediated by geopolitical considerations rather than purely economic ones, deepening inequalities and narrowing policy space. The rules-based order centered on the WTO continues to erode as major powers substitute bilateral deal-making and unilateral tariffs for negotiated disciplines, setting a precedent that encourages others to follow suit. In this environment, global corporations are compelled to redesign operations around two partially incompatible ecosystems. One is anchored in American standards, supply chains, and regulatory regimes, and the other in Chinese norms and infrastructures. This serves to reshape the geography of production, as well as the very architecture of globalization itself.

The AI Arms Race and the Struggle for Technological Sovereignty

The emergence of the internet has afforded the United States an unchallenged position as the world's foremost technological hegemon for nearly three decades, setting the standards, building the platforms, and defining the rules of the digital age. This dominance has now entered a new and more volatile phase with the rise of artificial intelligence, particularly in the form of large language models and generative AI systems that can influence everything from financial markets to military planning. The AI domain has rapidly become the latest field in which great powers seek to cement their status, with the United States and China emerging as the two primary contenders. American firms still lead the race, having produced roughly three-fifths of the most capable AI models currently in existence, but Chinese firms are catching up, accounting for about a quarter of top-performing systems and steadily closing the gap year by year.

The difference in approaches between the American and Chinese AI ecosystems is critical for understanding the geopolitical implications of this competition. American strength in AI is built upon a long-standing edge in semiconductor design, a vibrant software development culture, and a deep pool of risk-tolerant venture capital, all of which have facilitated massive commercialization of AI systems at global scale. China, constrained by sanctions and export controls on cutting-edge chips, has responded by pushing for more efficient model architectures, leveraging open-source tools, and building systems that can run on less capable hardware. Ironically, American attempts to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductors have spurred a wave of Chinese innovation, with engineers finding creative methods to deploy large models on inferior infrastructure, thereby reducing China’s vulnerability to future controls. Going into 2026, the expectation is therefore not of a frozen hierarchy in which the United States maintains permanent technological overmatch, but rather of a dynamic rivalry in which the performance gap narrows and both sides adapt rapidly to each other's moves.

Amidst this bipolar contest, a loose constellation of AI middle powers has begun to emerge, intent on avoiding total dependence on either Washington or Beijing for critical digital infrastructure. In Europe, the United Kingdom and a handful of continental states have invested heavily in hyperscale data centers and sovereign cloud solutions, marketing themselves as neutral platforms for AI development and deployment within a more regulated environment. Switzerland’s Apertus initiative, South Korea’s industrial AI programs, and Taiwan’s own AI sovereignty push illustrate a broader trend of states seeking to build domestic model stacks, data governance regimes, and compute capacity that can function independently of US or Chinese platforms. What began as a race to train the largest language models has therefore started to spill into adjacent domains such as semiconductor design and quantum computing, creating a more complex technological battleground in which these middle powers seek opportunities to carve out their own niches of influence.

Underlying these strategic ambitions, however, is a brittle web of physical and human dependencies that make AI both a tool of power and a source of vulnerability. On the hardware side, global capacity to produce the most advanced chips is heavily concentrated. Taiwan's emergent foundry manufactures the overwhelming majority of cutting-edge semiconductors, while much of the design work remains dominated by American firms such as Intel, NVIDIA, and Qualcomm. Data centers, which are essential for training and running large models, consume vast amounts of electricity and water, turning energy security into a central concern for any state that aspires to AI leadership. China continues to command an overwhelming share of rare earth mining and processing, granting it leverage over key inputs for high-performance computing and green technologies alike. Meanwhile, the United States still attracts many of the world's top AI researchers, draining expertise from other regions, while governments increasingly contest where data can be stored, processed, and exploited, framing questions of data residency and privacy as matters of national sovereignty rather than mere commercial regulation.

Artificial intelligence is a domain of competition and a force multiplier for many of the most destabilizing instruments of statecraft. Generative AI lowers the cost and raises the sophistication of cyber operations, enabling attackers to craft tailored phishing campaigns, optimize malware, and automate reconnaissance against critical infrastructure, research institutions, and governmental networks. The same tools that can generate convincing essays or images on demand can be repurposed to flood information environments with disinformation, deepfakes, and propaganda, complicating the ability of societies to establish a shared factual baseline in the midst of crises. Authoritarian governments have already integrated AI into vast surveillance architectures and credit-scoring systems, enhancing their capacity to monitor, profile, and preempt opposition. At the same time, militaries are experimenting with autonomous or semi-autonomous weapons platforms and AI-augmented command-and-control systems, introducing new uncertainties into doctrines about escalation and human control over lethal force. Looming on the horizon is quantum computing, in which the United States and China are again primary competitors, promising to shatter existing encryption standards and grant whichever side moves first a potentially decisive intelligence advantage.

In response to these developments, legal and regulatory frameworks around AI are fragmenting, deepening the division of the global digital ecosystem into rival blocs. The European Union has moved furthest in codifying a comprehensive AI regulatory regime, with its flagship legislation placing strict obligations on high-risk systems and emphasizing transparency, safety, and fundamental rights in ways that diverge sharply from the more laissez-faire American approach and the state-security-driven Chinese model. Rising demands for data localization, in which governments require that certain categories of data remain within national borders, are fracturing cloud architectures and complicating cross-border service provision. Export controls targeting advanced chips, models, and training tools have likewise turned access to AI-enabling technologies into a tightly managed geopolitical instrument rather than a neutral market transaction. As 2026 progresses, the regulatory divergence between Washington, Brussels, and Beijing is likely to widen, with each center attempting to impose its own standards for training data, safety protocols, and transparency on its sphere of influence, thereby embedding geopolitical competition into the very technical fabric of AI systems.

For private actors, these trends collectively mean that the era of the single global AI product is drawing to a close. Technology firms are increasingly compelled to design and maintain separate model instances, data pipelines, and compliance regimes for different jurisdictions, operating effectively in two or three partially incompatible regulatory and supply ecosystems. For developing nations, the picture is even more troubling. Lacking the fiscal capacity to build their own compute infrastructure or attract top-tier research talent, they risk being locked into dependency on external platforms, widening the AI capability gap and forcing them into difficult choices about alignment with American-centric or China-centric standards. From a security perspective, the spread of AI-enabled cyber tools and disinformation capabilities is outpacing the development of defensive mechanisms and norms of responsible use, increasing the probability that future crises will be accompanied by digital chaos that impedes effective decision‑making. The opacity and complexity of many cutting-edge AI systems also mean that political and military leaders may end up relying on tools they do not fully understand, raising the risk of miscalculation in high-stakes situations. Moreover, as AI systems automate more cognitive tasks, labor markets will struggle to adjust, with entire categories of white-collar work vulnerable to displacement and few credible large-scale retraining strategies in place. Finally, the massive energy requirements of AI and data center infrastructure will push governments to reconsider their energy policies and partnerships, enhancing the geopolitical leverage of energy exporters and tying the future trajectory of AI to decisions about grids, fuels, and climate commitments in ways that are only beginning to be appreciated.

Conclusion

The picture that emerges from 2026 is of a world in which geopolitical risk is no longer a series of isolated flashpoints but an overlapping system of mutually reinforcing shocks. The erosion of the post-Cold War security order, the normalization of coercive economic statecraft, and the weaponization of emergent technologies all point towards a decade in which volatility, not stability, is the baseline condition for international politics. For states, this means that the luxury of treating Ukraine, Taiwan, trade wars, and developments in AI as discrete files has vanished. Each factor now shapes the others in ways that can rapidly outpace bureaucratic and diplomatic response times. For businesses, the implication is starker still. Political risk has migrated from the periphery of strategy into the heart of balance-sheet calculations, dictating not just where firms can operate, but also what they can build, who they can sell to, and how resilient their supply chains must be in the face of sudden disruption.

From a commercial perspective, several sectors stand out as both beneficiaries and potential casualties of this emerging order. Defense and dual-use technology firms are likely to experience sustained demand as NATO grapples with the need to rearm, Indo-Pacific states prepare for potential cross-strait or South China Sea contingencies, and middle powers from Eastern Europe to the Gulf accelerate procurement of drones, air defenses, and electronic warfare capabilities. Semiconductor manufacturers, chip design houses, and the broader advanced manufacturing ecosystem will remain structurally critical, with any disruption to Taiwanese fabrication or tightening of US-China technology controls reverberating across automotive, consumer electronics, and AI-dependent services. Energy companies, especially those operating in LNG, nuclear, and grid infrastructure, are poised to gain from the re-politicization of energy security, as Europe continues to wean itself off Russian hydrocarbons, and data center proliferation drives up electricity demand worldwide. At the same time, firms in trade-exposed manufacturing, logistics, and consumer goods must prepare for a world in which tariff schedules, sanctions lists, and export-control regimes can shift with each diplomatic crisis, forcing costly re-routing of supply chains and constant reassessment of market viability.

Equally important are the industries that will sit at the intersection of humanitarian strain and political fragmentation. Agribusiness, water infrastructure, and insurance will face mounting pressure as climate‑driven shocks and conflict in regions such as Sudan, the Sahel, Gaza, and Yemen push food systems and urban resilience to the breaking point, while donor fatigue and fragmented aid mechanisms leave more of the burden on private actors and local authorities. Companies in telecommunications, social media, and cloud services will find themselves pulled ever deeper into the politics of information control and data sovereignty, as governments across all regime types seek to regulate platforms, localize data, and carve out sovereign digital spaces in which foreign providers are either heavily constrained or excluded outright. For investors and corporate strategists, the core lesson of 2026 is that sectoral due diligence must now be married to geopolitical scenario planning. Resilience will belong not to those who can predict which single crisis will erupt next, but to those who build portfolios, supply chains, and governance structures capable of withstanding a world in which several such crises unfold at once, often in mutually reinforcing ways.

The views expressed in this article are strictly those of the authors unless attributed otherwise. They are speculative in nature, and should not be taken as being statements of fact. Any business or investment decisions that you choose to make should be based on comprehensive research; all said decisions carry exposure to all forms of risk.

Takamaro H. is one of the two founders of Autran Group. Having previously lived in (as of 2025) nine countries, he brings a global perspective to our firm; one which is vital to being able to understand the implications of the constant state of flux that our world finds itself in. He is personally invested in the intersection of law and business, and regularly researches novel developments in the legal field. Takamaro created Autran Group after his experience in establishing and managing import-export businesses, wherein he observed that there was a gap in relation to companies’ ability to manage geopolitical and regulatory shifts. Apart from his legal and business interests, Takamaro is also highly passionate about history and linguistics; besides his native English and Japanese, Takamaro also speaks French, Italian and Russian, with a moderate command of Spanish and Chinese.

Raymond P. is the Head Team Leader at Autran Group, and is a graduate of Florida International University. He is currently undertaking a Master's Degree in Communications and Public Relations, and specialises in Middle Eastern and Latin American Affairs. Raymond speaks English, Spanish, and Arabic, with a moderate command of French.